We usually kick off this year-end report with a “Happy New Year” greeting. And while we do indeed wish all our clients the very best for 2025, this very young new year has not been a happy one here in our home base of Los Angeles County. Wildfires have destroyed the homes of many clients, business associates, and friends. Others are displaced from their surviving homes for an indefinite period. And virtually everyone in California knows someone severely impacted by the fires. The trauma is both deep and wide. If you have been affected by these terrible fires, please know we are here for you in whatever ways we can help.

A Year of Market Divergences

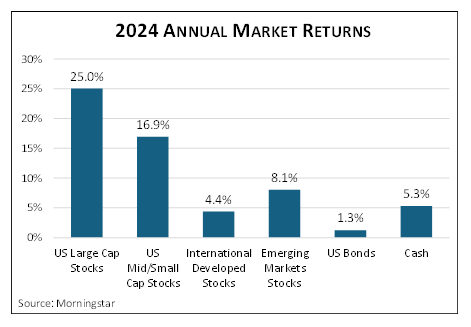

2024 was a good year for most investors despite very mixed performance across asset classes, thanks to another unusually strong year for US large cap stocks. The bellwether S&P 500 returned a whopping 25% last year, leading all major stock categories, so even a moderate allocation there lifted overall portfolio returns. US mid/small cap stocks also did very well, returning nearly 17%, while international developed and emerging markets stocks lagged substantially, gaining only about 4% and 8%, respectively.

Meanwhile, bonds eked out a small gain for the year. Though the Fed cut short-term interest rates, a variety of factors pushed long-term interest rates upward, causing the price of existing bonds to drop. The leading US bond index returned 1.3% , as bond interest income was enough to more than offset price declines.

Lessons for Exuberant Times

The S&P 500’s 25.0% return last year followed a similarly heady 26.3% return in 2023, giving the index its best two-year run since 1997-98 during the nascent internet’s “dot-com” boom. In case you’re wondering, the S&P 500 jumped another 21% in 1999 before peaking in March 2000, from which it shed about half its value in the ensuing 2-1/2 years.

Therein lie lessons. First, we can see that periods of (probably) unsustainably high returns (for example, 20%+/year) tell us very little about what the market will do in the coming year. The 2023-24 party could continue as in 1999, or it could abruptly end as in 2000. The same is true for 2025. Don’t try to time markets.

Second, all booms eventually run out of steam. While the internet was indeed a transformational development, it did not mean infinitely growing profits for businesses benefiting from the new technology. Similarly, AI today offers the possibility of radical change (for better and/or worse), but the combination of competition and finite consumer demand means AI stocks will not become the first proverbial trees to grow to the sky. Don’t get carried away.

We commonly see “recency” bias in how investors evaluate risk. This habit starts early. Company president Don Gould recounts a story from his childhood.

“When I was six years old, the neighbor boy across the street, Walter, invited me over to play with Christmas presents he had just received. Walter’s family had recently moved from Texas to suburban LA, his father a transplanted oil company executive. We were both big fans of the rugged steel Tonka toy trucks, and Walter had struck gold, Santa having delivered the coveted new safari Jeep with its signature candy-striped plastic canopy.

“Walter’s backyard sloped steeply downhill, with a switchback concrete path wending its way through landscaping down to the Rubio Wash, one of LA County’s many flood control channels, at the bottom. Standing at the very top on the back patio, Walter grabbed an older beat-up Tonka jeep of his and gave it a mighty heave down the slope, throwing it like a discus. Miraculously, the jeep landed on the concrete path, squarely on all four tires, unmarred, not unlike an Olympic gymnast “sticking” the landing. Whereupon Walter handed me his new safari jeep and insisted I do the same. Already attuned to concepts of risk and return at that early age, I protested. “You were just lucky with that throw. I’m not gonna throw your new jeep.” Walter would have none of it. The more I resisted, the angrier he got. “It’s MY JEEP and I WANT YOU TO THROW IT DOWN THE HILL!” I suspect my last thought as I let it fly was, yes, it’s your jeep. I’m not sure how or where the safari jeep landed. All I clearly remember is the candy-striped plastic canopy disintegrating upon impact.

“There followed much recrimination, Walter crying over his shattered jeep, me crying over my reluctant role in the disaster, and Walter’s mother Sophie coming out of the house to sort out all the commotion. I pleaded my case, and she wisely sent me home until cooler heads could prevail.”

Walter had understandably concluded from his recent experience that throwing Tonka jeeps was both fun and without much downside risk. Investors often do a similar thing after an extended period of rising stock prices, either underestimating market risk or overestimating their tolerance for the risk.

Investment discipline is the only protection from both our inability to predict the outcome of the market’s next toss and the natural emotions of greed and fear. That discipline includes diversification—today’s winners and losers could quickly swap places—and rebalancing, which helps see that neither bull nor bear markets cause your portfolio to drift away from one that meets your long-term objectives.

What’s Next for Markets

We cannot remember a year-end during which so many have asked our stock market forecast for the coming year. Perhaps it is uncertainty surrounding the change in administration in Washington, but whatever the cause, people seem more curious than usual. We don’t subscribe to the common Wall Street practice of making market forecasts, a futile exercise usually cloaked in a phony aura of expertise and jargon. We have various quips in response to the question of where the market is next headed, such as, “if we knew that, we wouldn’t have to work for a living,” or the more straightforward, “I don’t know.”

That said, we can still highlight factors that could help or hurt the stock market in the year ahead. Two stand out. Lower tax rates and lighter regulation—expected outcomes of November’s election results—tend to help corporate profits, a primary driver of stock prices. Many credit this with the stock market’s rise in the first month after the election.

On the converse side, long-term interest rates have moved significantly higher since the election, perhaps indicating concern that we are entering a period of less fiscal restraint, leading to higher deficits, a more rapidly growing national debt, and higher inflation. Higher bond yields are usually (but not always) a drag on stock market performance, and this has been the case for most of December and the first half of January.

The net effect of the two countervailing forces in the ten weeks since the election has been an essentially flat US stock market.

For a fuller discussion, be sure to see our Q4 Economic & Market Review.