by Don Gould

From an early age we are admonished, “don’t keep all your eggs in one basket,” especially where investments are concerned. A diversified investment portfolio holds many assets rather than just one or a few, greatly reducing the chances that all your eggs go Humpty-Dumpty at once.

For example, it’s a lot less risky to own an S&P 500 index fund, which spreads your risk across 500 companies, than to keep your whole portfolio in one stock. Notice I am not saying the diversified portfolio will necessarily do better than the single stock.

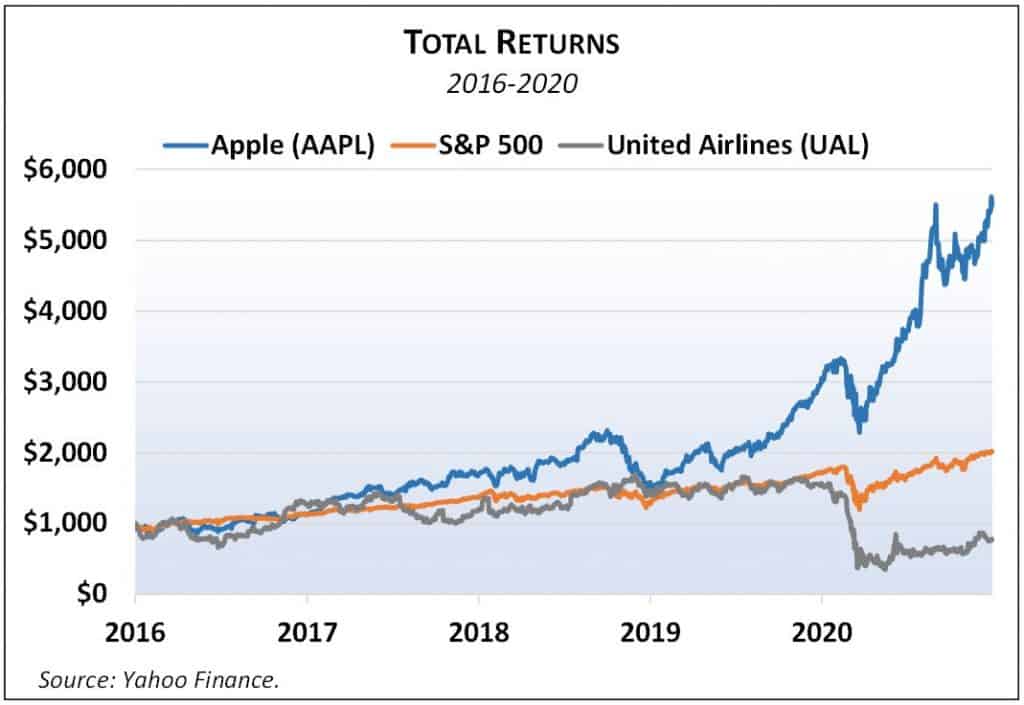

Imagine that you invested $1,000 at the start of 2016 and held on for five years. If you put it all in the broadly diversified S&P 500, your stake would have grown to about $2,000. Putting it instead in a single stock could lead to a very different outcome. For example, if you concentrated it all in Apple, you’d have a whopping $5,000 at the end. Conversely, if you bet on United Airlines, you’d have only $900. Alas, we know this only after the fact. And as obvious as everything seems in hindsight, I can assure you that the consensus expected return on both stocks was about the same five years ago.

The takeaway is that the diversified portfolio was considerably less risky. The investor was assured of closely matching the market’s overall performance, without the risk of hugely underperforming the market as did United Airlines.

Layers of Risk

Stock risks are broken down into two general categories. The first is “idiosyncratic” risk, which is specific to a single company. If you diversify sufficiently, you can avoid idiosyncratic risk because it is random by nature. For every United there will be an Apple in the portfolio to balance things out.

Boeing’s recent safety issue with its 737 Max aircraft is a case of idiosyncratic risk. The problem was specific to Boeing, though it did ripple to some airlines and Boeing subcontractors. Even so, Boeing did not pull the whole market down with it.

The second type of stock market risk is called “systematic” risk, the risk that the whole market goes down at once. We saw systematic risk at work when the market dropped 34 percent in the early days of the pandemic. But even systematic risk in one asset category (such as stocks or bonds) can be mitigated if you diversify across asset categories. Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) is a framework that helps investors get more precise about how many categories to own and how much to hold in each.

MPT considers the correlation between the returns of the assets you own. Ideally, you own assets whose returns don’t move together—X zigs when Y zags. For example, bonds and gold don’t usually move much in sync with stocks. Real estate is another form of diversification, though both real estate and stocks are vulnerable to a general economic downturn. In theory, with MPT you can construct an “optimal” portfolio—one that gives you the highest available expected return for the level of risk you are willing to take on.

Hidden Risks

Other less obvious forms of correlation can sneak into our lives and expose us to significant financial risk. Suppose, for example, that you have a good paying job with a successful company. A big part of your compensation might come in the form of company stock, which could represent a large and growing percentage of your total assets over time.

The problem? Your job security and your portfolio both depend on the company’s continued success. If the company stumbles, you could find yourself unemployed and your savings diminished when you can least afford it. The Texas energy company Enron was a glaring case study—employees held most of their company-sponsored retirement plan assets in Enron stock. When Enron collapsed amid scandal, employees lost both their livelihoods and their assets. Enron employees who held diversified portfolios at least had something to fall back on while they searched for new opportunities.

Similarly, investors who focus on real estate may feel diversified by owning several different rental properties. But if the properties are all in the same general vicinity and close to one section of the San Andreas fault, they share a highly correlated risk. A single earthquake could devastate all the properties at once.

This story ends as it began—don’t keep all your eggs in one basket. Spread them across many baskets made of a variety of materials and carried by different people on different days of the week. With a little luck, when the weekend arrives, you’ll be able to enjoy an omelet.

Don Gould is president and chief investment officer of Gould Asset Management.