Inflation Returns, But for How Long?

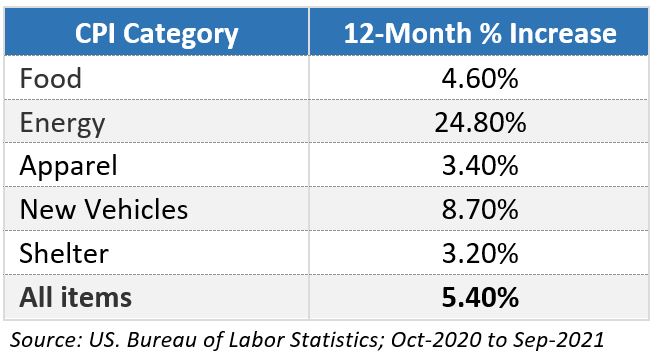

Inflation is back. You can see it at the grocery store, in restaurants, wages, housing costs, gasoline, and many other places. Inflation also manifests in a more subtle way—getting less for what you pay. Have you noticed that the same postage stamp buys slower delivery of your birthday card? Or that you must wait longer to get served in almost any retail setting?

Of the many rules of economics we were once taught, the role of supply and demand in determining prices is one that has survived intact. A drop in supply, rise in demand, or a combination of the two will push prices higher, restoring the balance between the quantity of goods and services supplied and consumed.

Let’s start with a look at the demand side, using the US as an example. Understandably, at the pandemic’s outset both Congress and the Federal Reserve were willing to use every tool at their disposal to avoid a pandemic-induced economic depression. Trillions of dollars of fiscal and monetary stimulus largely achieved that aim. Demand levels today are well above their 2020 lows and probably not too different from their heights of two years ago.

The Broken Supply Chain

The problem is, the pandemic has taken a sledgehammer to global supply chains, that network of raw materials, labor, manufacturing, and transportation that puts a product on the store shelf. You may recall, not so long ago, businesses boasted of meeting consumer demand “just-in-time.” While efficient at minimizing product inventory, factory capacity, etc., thereby improving corporate profits, just-in-time processes also left no margin for error when supply chains are disrupted.

Likewise, globalization—sourcing the cheapest labor and materials worldwide—has been lauded for cutting prices and boosting profits. The flip side of globalization is that the US, for example, no longer produces many essential items domestically. To take one case, about 80% of key pharmaceutical components are made exclusively abroad. The upshot is that when activity halts in one part of the world, its effects ripple globally.

Suddenly it seems everything is in short supply. Take cars as one case study. Today’s vehicles are computers on wheels, heavily dependent on a variety of chips to operate. Covid outbreaks have repeatedly shuttered chip factories in Asia, leaving auto manufacturers unable to push enough cars to the showroom to meet buyer demand. The result: new cars routinely selling well over sticker price and empty dealer lots.

Perhaps most worrisome is a persistent labor shortage, a surprise to many who thought that idled workers would return to the workforce at their earliest opportunity. Instead, the pandemic has been a wake-up call to many—perhaps a reminder that life is finite and one should be as selective as circumstances permit in deciding if and where to work.

Some call this the “Great Reassessment.” Many baby boomers have retired ahead of schedule. Former restaurant workers now perceive that work as both stressful and unstable. Higher wages don’t seem to be enough to fix this—$40,000 per year dishwasher jobs are going unfilled. Smaller businesses, lacking scale, seem hardest hit. Help wanted signs are everywhere, often next to a hand-lettered sign advising of reduced store hours.

Other factors are at work, too. For example, women are returning to work at a significantly slower rate than men. This might reflect the disproportionate share of childcare duties taken on by women, the uneven process of kids returning to school, and the high cost and limited availability of childcare for pre-kindergarten children.

When a business can’t get all the workers it needs and must pay more for those it can get, the result is higher prices for the end-product, and less of it.

And as if on cue, energy prices have spiked, reminding us of the oil crises that exacerbated inflation in the 1970s. Energy supplies have not kept up with rebounding consumer demand. A big reason: climate change and the transition to renewable energy have made fossil fuels both less desirable and available. Factories in China have curtailed operating hours due to electricity rationing, further straining supply chains.

Why Inflation Matters to Investors

We often look at our portfolios as an end in themselves, but in fact portfolios are like batteries, storing purchasing power for consumption at a later date. Like a battery losing some of its charge, inflation erodes the purchasing power of assets, making our portfolios less valuable in real terms. Long-term fixed rate bonds are especially vulnerable to unanticipated inflation because the interest and principal they pay is a fixed dollar amount, even as the dollar buys less each year.

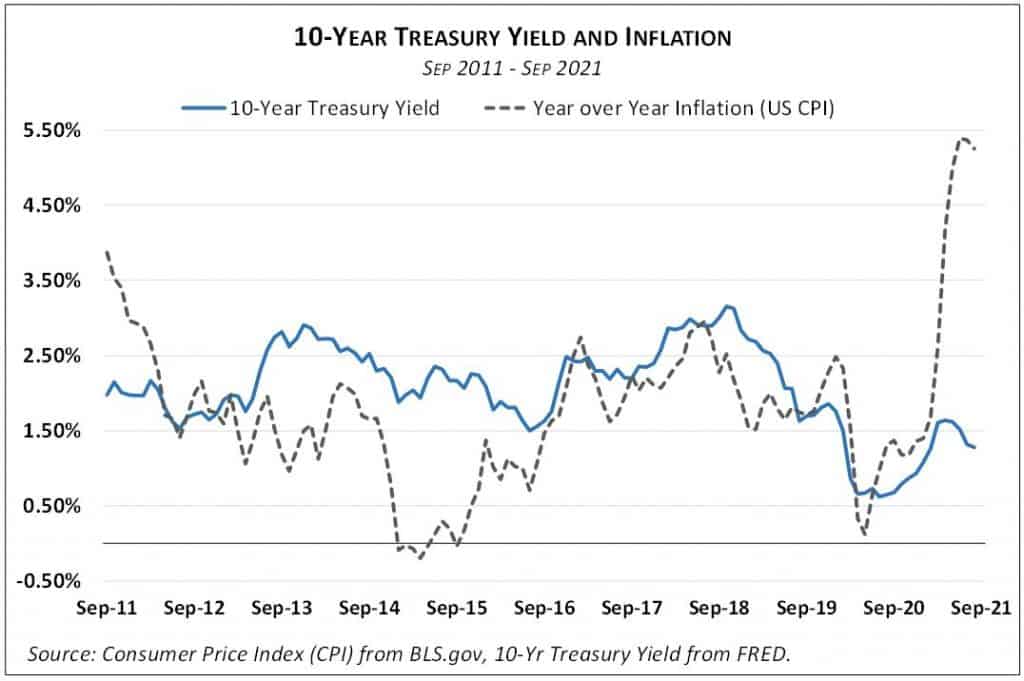

In a normally functioning market, investors facing higher expected inflation demand a higher interest rate on new bonds to compensate for the more rapid loss of purchasing power over the bond’s life. In turn, this pushes down the price of existing bonds, elevating their yields to keep them competitive with new bonds.

Meaningfully higher bond yields could also adversely affect the price of riskier assets such as stocks and real estate, whose required returns (and therefore prices) are calibrated to the available yield on less risky assets such as bonds.

The accompanying chart shows that despite a bounce from last year’s pandemic lows, bond yields have not nearly kept up with inflation. Instead, long-term Treasury yields remain near historic lows. We can think of two possible explanations. One is that the market accepts the Fed’s assertion that the inflation jump is transitory, and inflation will drop to pre-pandemic levels relatively soon. The other is that the market expects inflation to really be higher than recent norms, but expansive monetary policy (including central bank open-market bond purchases; so-called Quantitative Easing or QE) is artificially depressing bond yields worldwide.

Whether this jump in inflation is long-lasting or just a blip may depend in part on psychology. If people believe inflation is back to stay, contracts will start to build in that assumption, creating a feedback loop that makes higher inflation a self-fulfilling prophecy.

No matter how this plays out, we must acknowledge that inflation meaningfully chipped away at portfolios’ purchasing power in the last year. We are watching this development closely.