Fourth Quarter Reprieve Can’t Fix 2022

Stock and bond markets bounced back in the fourth quarter. Global stock benchmarks climbed about 10%, while the leading US bond index gained about 2%. The recovery was largely fueled by a modest decline in bond yields; more on that below. Unfortunately, the fourth quarter’s upturn was not nearly enough to rescue one of the most challenging investing years in memory.

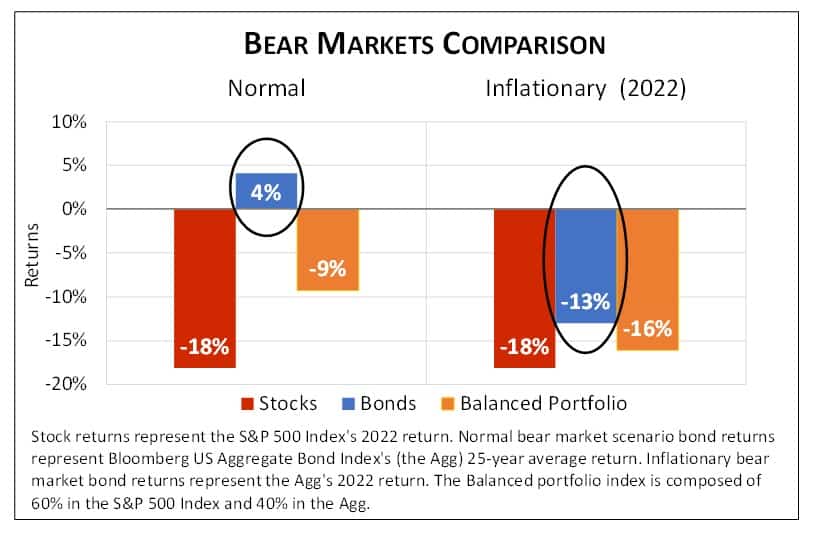

How challenging? It was only the third time in the last 96 years that both stocks and bonds were down in the same calendar year, the previous two being 1931 and 1969. A benchmark of 60% US large cap stocks and 40% US bonds turned in its fourth worst year ever (down about 16%), eclipsed only by two years in the Great Depression and 2008, year of the Great Financial Crisis.

In most bear markets, the bond portion of a balanced portfolio substantially reduces portfolio risk. 2022, however, witnessed the rare inflationary bear market. The accompanying chart illustrates how such an environment can wreak havoc on the balanced portfolio.

The Bond Markets Most Dismal Year

While the roughly 18% decline in both US large cap and global equity indexes was painful, it was well within the range one expects in a bear market, and nothing close to 2008’s 37% decline in the S&P 500. Bonds were the real outlier last year and the main reason balanced portfolios fared so poorly. The leading US bond index dropped 13% last year—it was by a wide margin the worst year ever recorded for this asset class. Understanding bonds’ poor 2022 performance requires a look at both the components of bond returns and the larger macroeconomic backdrop.

A bond’s total return in any period is simply its interest payments plus any change in its price. Recall that the price of an existing bond moves inversely to changes in market interest rates. When rates rise, the price must drop to keep the existing bond’s expected return (its “yield to maturity”) equal to that of the new higher interest rate bonds.

Bond returns suffered on two counts last year. First, rates were very low to begin the year, still reflecting early pandemic policy. The 10-year US Treasury yield began the year at 1.52%. This meant that the interest component of bond returns was small and provided little cushion against the large bond price declines that ensued as interest rates soared last year. Fed actions in 2022 pushed up interest rates on bonds of all maturities, seeking to slow the economy and thereby put a damper on inflationary pressures. The 10-year US Treasury yield closed the year at 3.88%, a rise that translated into a nearly 18% drop in the bond’s price, which swamped the small amount of interest earned.

Last Year’s Bad News is Hopefully This Year’s Better News

While it is impossible to predict this (or any) year’s stock market return, we do think bonds are much more likely to provide portfolio protection in 2023. Taking the US 10-year Treasury again as an example, we know with near certainty that the bondholder will earn nearly 4% in interest over the course of the year. Should rates continue to climb, that 4% is a much bigger cushion against bond price declines than was available a year ago. Also, with a recession potentially in the offing and inflation showing signs of moderating, we think that any further increase in interest rates (and associated bond price declines) will likely be muted when compared to 2022.

If we’re right, then at a minimum, bonds will dilute equity market risk in 2023. And there’s a reasonable chance that bond returns will swing back into the black this year, meaning they could add to the balanced portfolio’s return.

On the equities side of the coin, the stock market had nearly everything going against it in 2022. It started with a market where many of the highest fliers had already begun their descent as much as a year earlier, in early 2021. As we noted here a year ago, a steadily shrinking list of the largest cap stocks led the market to its all-time high at the end of 2021. This declining “breadth” often portends trouble. The Fed’s monetary tightening pushed up interest rates, helping bonds compete with stocks for the first time in ages. Higher rates have also had their intended effect of slowing the economy and raising the odds of recession (and lower corporate earnings) in 2023, further weighing down stocks last year. The market also lost its manic aspect last year as the air was let out of many of the most speculative corners of the investment world, such as Tesla stock and cryptocurrencies. Finally, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last February started a war that continues to hamper the global economy today. Potential good news for stock markets could be that in a recession, equities tend to turn upward well before the economy bottoms. Most observers expect any recession to run its course in 2023, in which case a sustained upturn in stock markets could begin sometime this year.

An Aerial View of the Turbulent Pandemic Years

It is both easy and natural to remember most clearly whatever has happened most recently, whether that’s politics, markets, our personal lives, or something else. Cognitive psychologists call this “recency bias.” For investors, 2022’s very challenging markets are likely top of mind. Part of our job as advisors is to help our clients keep the longer-term picture in view when looking both forward and back.

This mindset is particularly helpful in considering the last three years, a period dominated by the world’s first pandemic in a century. An aerial view of pandemic-era macroeconomic policy might be summarized as follows. Fearing a massive slowdown, the government slashed interest rates to near zero while also pumping trillions of dollars of fiscal stimulus into the economy. As the pandemic faded and the economy rebounded, inflation quickly took hold when labor markets and output could not keep up with soaring demand. In response, central banks slammed on the brakes, pushing up interest rates.

Investors endured a three year roller coaster ride with both the economy and financial markets. But in the end, after all the dust has settled, it’s remarkable to see that by economic and financial measures, the period as a whole was, well, average. Despite all the wild swings, the S&P 500 annual return for 2020-2022 was about 7.7%, not much below its long-term average. Similarly, as the accompanying chart shows, GDP ended the three-year period almost exactly on its long-term trend line—all this despite fears of both depression and runaway inflation within the period.

The moral of the story remains the same. Keeping our eye on long-term goals, consistent with our long-term time horizon, is the surest way to avoid overreaction in the moment.

For a fuller discussion, be sure to see our Q4 Economic & Market Review.