by Donald Gould

Almost from his first days in office, President Trump has been lobbying for lower interest rates. This has taken the form of the president’s consistent criticism of Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell for not lowering rates further, even musing about firing Powell before his term expires next year.

Presidents of both parties — from Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon to more recent administrations — have expressed frustration when Fed decisions did not align with their economic or political priorities. What makes today’s situation stand out is the unusually public and persistent nature of the criticism, along with open discussion about terminating the Fed chair.

Lower interest rates usually stimulate economic activity by reducing interest expense for all variety of borrowers, from homeowners with mortgages to businesses taking out loans for expansion or acquisitions. Rate cuts can also boost the stock market simply by making cash and bonds less attractive in comparison. And higher stock prices tend to increase spending by households that own stocks, further juicing the economy.

Political strategist James Carville, summing up a key to modern elections, famously said, “it’s the economy, stupid.” With midterm elections only a little more than a year away, President Trump is likely aware of how the economy’s vigor in 2026 might affect the balance of power in Congress.

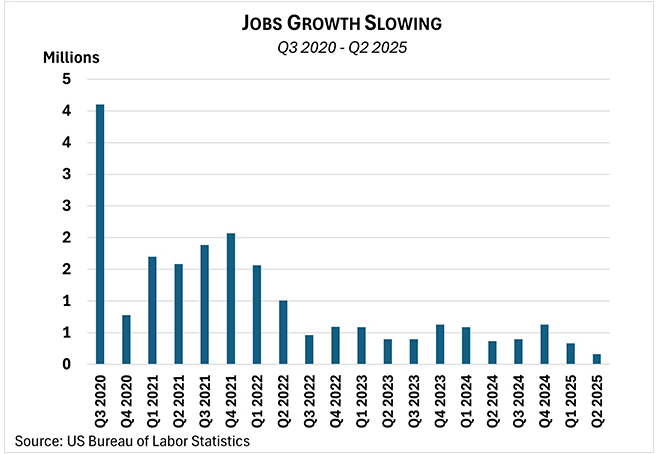

The Fed, however, has a broader set of priorities. Its dual mandate, established by Congress in 1977, is to promote both maximum employment and stable prices. These two goals often are at odds with one another, and that teeter-totter relationship puts the Fed in a bind right now.

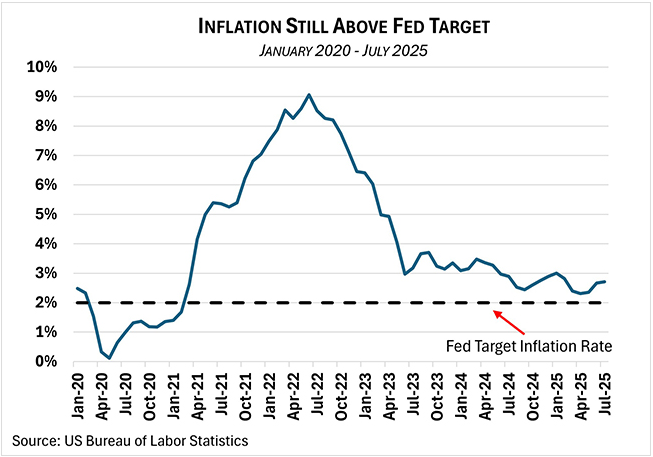

Inflation, though down sharply from its short-lived post-pandemic peak of 9%, is holding stubbornly above the Fed’s 2% target — currently closer to 3%. Arguably, current policies on trade and immigration are also inflationary. Meanwhile, recent jobs reports show significant slowing in new job creation. Despite the inflation risks, it appears likely the Fed will cut rates in its September 17 announcement, giving greater priority to its employment mandate for the moment.

The Fed was established as an independent agency so that political considerations would not drive monetary policy. A Fed heavily influenced by an administration’s short-term political priorities could, in theory, lose sight of its mandate to control inflation. Market watchers both here and abroad have expressed concern that President Trump’s criticism and threatened firing of Fed chair Powell, as well as his recent actual firings of Fed governor Lisa Cook (currently put on hold by a federal judge) and the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, threaten the Fed’s actual or perceived independence.

If bond traders — the so-called bond market “vigilantes” — lose faith in the Fed’s independence, interest rates on longer-term bonds could rise despite the Fed cutting short-term rates, as investors demand higher bond yields to compensate for the increased risk of elevated inflation. While the Fed sets short-term rates, which in turn influence long-term rates, ultimately the bond market determines interest rates on longer-term obligations.

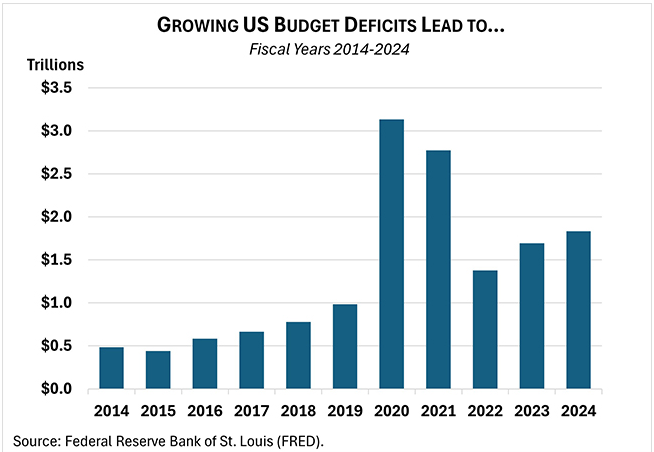

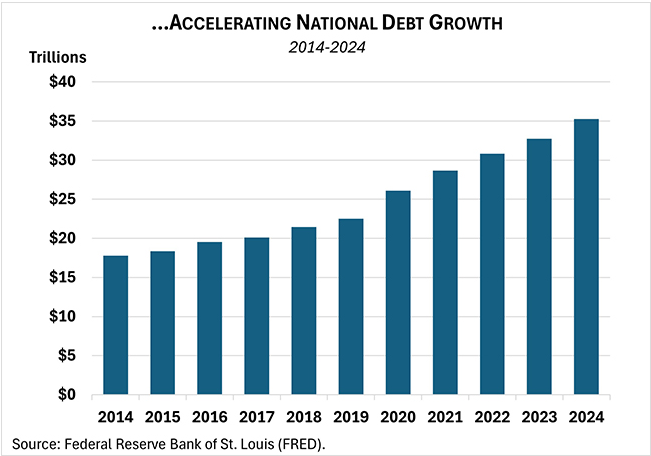

The other big worry surrounding long-term interest rates is America’s burgeoning national debt. The U.S. runs a large annual budget deficit, currently projected at nearly $2 trillion for fiscal year 2025. The U.S. Treasury must borrow that amount to pay the government’s bills, adding to an existing debt pile of about $37 trillion. The problem is that the debt plus the annual interest payments are growing faster than the economy. In a sort of vicious cycle, interest paid on U.S. Treasury debt is now the largest component of the federal budget — larger even than the defense budget — and rapidly rising.

Unless there are major budget cuts and/or tax increases, or the economy grows much faster than it has historically, the Treasury will need to issue ever more debt annually. Other things being equal, a growing supply of new government debt will push longer-term interest rates higher.

And yet … bond and stock market investors have so far largely shown little concern. The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury has fallen from 4.8% to near 4.0% since January, and the U.S. stock market is near record highs. Are markets whistling past the graveyard? Or is a new and brighter economy around the corner? Stay tuned.

Donald Gould is president and chief investment officer of Gould Asset Management of Claremont.