by Don Gould

Note: Before I write about money and investments in the context of the COVID-19, I want to be clear that the illness is first and foremost a health and humanitarian concern and only secondarily a financial one. As important an asset as money may be, health is always our greatest asset. Our thoughts go out to all affected by the illness.

The word “pandemic” immediately raises one’s anxiety. It seems like a conflation of “panic” and “pandemonium,” and those are apt words to describe the recent state of financial markets.

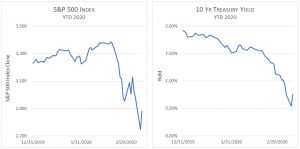

To recap, after reaching an all-time high on February 19, the US stock market began to reckon with the prospect of COVID-19 spreading globally. In the ensuing three weeks, the leading S&P 500 index shed about 19% of its value. More remarkable has been the nosedive in interest rates on US government debt over the same period. The benchmark 10-year US Treasury note yield fell from 1.57% to as low as 0.50%, as investors seeking safety above all quickly bid up their price (thereby pushing down their yield).

Concerns about an economic slowdown caused by consumers and workers holing up at home also have put pressure on commodity prices and caused at least a short-term fracture among the cartel of oil exporting nations. Earlier this week, the price of crude oil plunged more than 20%, a 50% drop from its January high.

It’s natural in times of volatile markets for investors to look to their investment advisor for answers. How much will the virus hamper the economy? How far down will the market go from here? When will it turn around? The honest answer: I don’t know and neither does any “expert” who claims otherwise.

What We Think We Know

We’ve seen many periods of market adversity over the decades, each with unique characteristics, including this one.

In the face of many unknowns, here’s what we think we know.

-

- Market turbulence will likely continue as events unfold.

- A COVID-19 pandemic can be thought of as a worldwide natural disaster, like a hurricane or an earthquake that works its way across the globe.

- Natural disasters quickly depress economic activity. The magnitude and duration of the impact depends on the nature of the disaster, but afterwards recovery is steady and often rapid.

- A pandemic exacts a profound toll on its victims and their families and friends. But in time it passes, and the world moves forward.

- Consequently, we can expect that economies and markets will eventually recover, though the time frame of such recovery remains uncertain.

Avoid Market Timing

Fear can tempt people to sell stocks in hopes of sidestepping further decline. In theory, you buy back later at a lower price.

In practice, virtually no one does well at this sort of market timing.

Case in point: in the 2007-2009 financial crisis, we saw a few investors bail out of stocks before the market reached bottom in March 2009. Their relief was short-lived—generally those who sold either never got back in or did so only after prices had climbed beyond the levels at which they originally sold.

In other words, even investors who managed to sell well before the market bottom ultimately gave up substantial gains. The costs were compounded for those who realized capital gains on their stock sales, increasing their tax bill.

Asset Allocation is Key

In the end, we always return to asset allocation. Why allocate some portion of your portfolio to often volatile stocks? Because in the long run, stocks have vastly outperformed safer alternatives like cash and bonds. So why not allocate all your portfolio to stocks? Because almost no one wants the entirety of their liquid assets subject to the kind of volatility we’ve been seeing.

The trick is finding the right balance between stocks and bonds—that is, between long-term growth and short-term stability. Investors vary in their portfolio size, time horizon, growth needs, and risk tolerance. As a result, the right asset allocation varies by investor and may also vary as one gets older.

Think of the “right” asset allocation as the one that enables you to stay the course, albeit with a tightly fastened seatbelt, through even highly volatile market environments.