by Don Gould

This is the second in a three-part series of reflections on changes in the investment industry in the 25 years since I started Gould Asset Management in Claremont.

In part one of this series, I described how core investment products such as mutual funds have become commoditized in recent decades, leading to ever lower fees and profits for fund management companies, but commensurately higher returns for their investor clients.

Of course, the Wall Street empire wasn’t going to let disappearing mutual fund profit margins go unanswered. To replace those lost profits, big financial firms have increasingly turned to more complex and less liquid investment products that can command higher fees. These include private equity and private debt funds, which invest in the securities of companies that do not trade on public markets, real estate funds, and so-called “hedge funds” that pursue esoteric trading strategies.

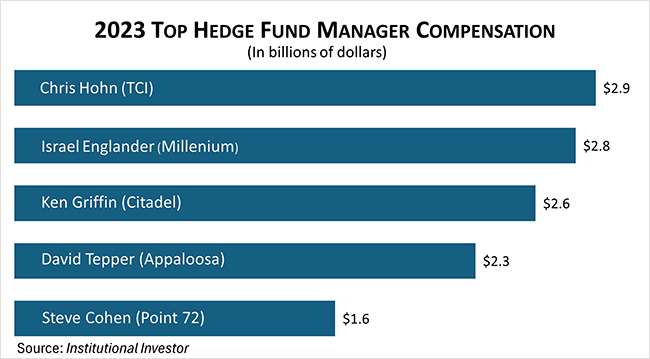

Some of these products are fabulously expensive, which is why you may have read about some hedge fund managers pulling down billions of dollars in annual compensation. It reminds me of the old joke about the tourists visiting lower Manhattan. Their guide points out one financier’s yacht after another. Finally, one rube asks, “Where are the customers’ yachts?”

Enter the index fund: investments get commoditized

The higher the fees on a product, the more skeptical you should be about the value you’ll receive. It is common for private equity and hedge funds to charge a base annual fee of 2% of assets, plus 20% of any profits. These fund managers argue that getting a cut of fund profits gives them an incentive to generate the biggest possible profits for investors.

A more cynical take: this is a one-sided bet squarely in the manager’s favor, not the client’s. If the fund performs great, the manager does extremely well, and the client perhaps does well enough. If instead the fund performs badly, the investor shoulders all the losses.

Don’t get me wrong: these products have their place in a diversified portfolio, but it’s always important to keep an eye on costs. Often, the costs are too high to justify the potential benefits. And sometimes a similar investment can be found in a liquid form at a lower cost.

Innovations: a mixed bag

One of the more useful financial product innovations of recent years are funds whose returns are not highly correlated with either the stock or bond markets. A portfolio reduces risk by including components that don’t all move in the same direction at the same time. That’s the point of diversification.

An example of such a product is catastrophe bonds. (Granted, not the most inviting name for an investment.) These bonds are sold by property-casualty insurance companies looking to off-load some of their risk exposure from, say, an extraordinary major hurricane. “Cat” bonds chalk up steady returns in most years, but face substantial losses in the event of a Hurricane Katrina type event. The timing of natural disasters generally has very little correlation with the economy or financial markets, so purchased in proper quantities, catastrophe bonds can be a good portfolio diversifier.

Another innovation is the so-called “structured note,” an investment product whose return and risk characteristics are very different from an ordinary stock or bond. Large banks and brokerage firms use complex quantitative techniques to engineer these unnatural investments into being and sell them to the investing public. The notes usually offer a deal that sounds attractive, but no amount of financial wizardry can improve the fundamental tradeoff between risk and return.

As an example, a structured note might have a three-year term, over which it pays you the gain of the S&P 500 stock index (if the market goes up), up to a maximum of 25%, and protects you against the first 20% loss on the index (if the market goes down). It’s clear you are giving up some upside return potential for some downside protection, but even very sophisticated investors cannot evaluate whether this is a fair deal. Similarly, it’s nearly impossible to measure the underlying expense the sponsor has built in as compensation for structuring the product. All are reasons to steer clear.

I’ll conclude with an innovation that seems positive for investors, but is at best a mixed blessing. About 10 years ago, upstart broker Robinhood began offering zero-commission stock trading. Eventually, this forced larger competitors like Charles Schwab to follow suit. To make up for lost commission revenue, Schwab now sweeps clients’ idle cash balances into a bank deposit that today pays 0.20% at a time when Schwab’s own money market funds are paying about 4.70%. The spread between the two generates billions of dollars of annual revenue for Schwab, reducing their customers’ returns dollar for dollar.

With every innovation that works to investors’ favor, it seems that the Wall Street empire finds a new way to regain its profits. Stay nimble, and may the force be with you.

Next up is Part III: lessons learned over the past 25 years.

Don Gould is president and chief investment officer of Gould Asset Management of Claremont.